Japanese cars were once a risk. “As with most imports,” Consumer Reports wrote in a 1970 five-way test of sports cars, including the Datsun 240Z, “finding parts and service may be difficult, especially outside the larger metropolitan areas. And therein may lie the justification for buying one of the sports cars in this group other than the Datsun. If you don’t have a competent Datsun dealer nearby, you should consider one of the runners-up.”

This story originally appeared in Volume 13 of Road & Track.

SIGN UP FOR THE TRACK CLUB BY R&T FOR MORE EXCLUSIVE STORIES

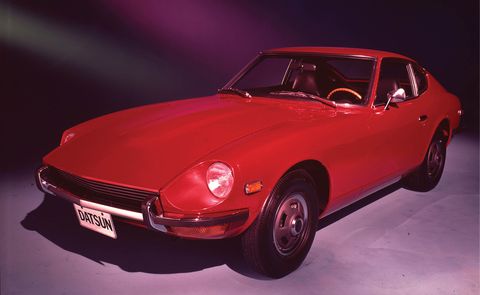

The first Z-car, the clearly superior 1970 240Z, almost single-handedly validated Japanese cars in the minds of consumers. It was attainable glamour. Uncompromised. An E-type for Mustang money, an E-type with reliability.

Today, duh, the Japanese brands have plenty of dealership support. The question is whether anyone cares about mid-priced, two-seat sports cars anymore. The 2023 Nissan Z’s job is merely to sell.

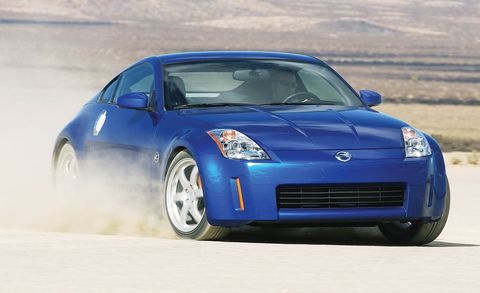

The RZ34 Z’s looks clearly recall the previous six generations of Z-cars, and much of its foundational engineering is shared with the outgoing 370Z. So the temptation is to consider this new car a simple continuation of the species. But it’s not. It has a different nature, more indomitable and less winsome. The reason is torque.

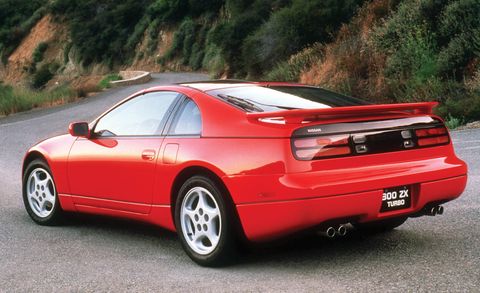

There have been turbocharged Z-cars before, starting with the 1981 280ZX. But this numberless Z is the first since the Z32-generation 300ZX Twin Turbo was dispatched in 1996. And this is the first Z available only with a turbo.

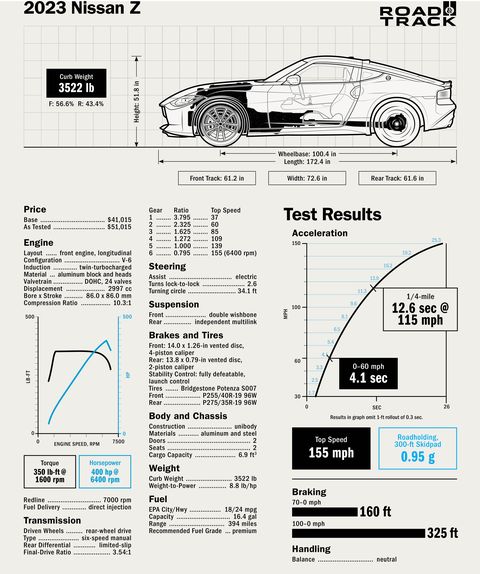

It’s a modern, 21st-century turbo engine too. This is a version of the VR30DDTT 3.0-liter V-6 that first appeared back in the 2016 Infiniti Q50 sedan. It’s not an engine built for sports-car antics, but a four-cam, direct-injected, variable-timed 24-valve unit that is used in luxury sedans and SUVs latched to easygoing automatic transmissions. While it’s rated at 400 hp, the biggest number with which any Z has been blessed, what matters is torque. This engine makes a consistent 350 lb-ft of grunt between 1600 and 5200 rpm, even though peak horsepower comes up at 6400 rpm (600 rpm short of redline). It’s that torque production that defines the new Z’s character.

The original 240Z’s 2.4-liter straight-six, breathing in through two Hitachi-made SU carburetors, made its 145.7 lb-ft at 4400 rpm and didn’t make much below that. The 151 hp came on at 5600 rpm, when the engine was about to strangle itself. The 1996 300ZX Twin Turbo’s 300-hp 3.0-liter V-6 generated 283 lb-ft of torque at 3600 rpm. All the previous Z-cars were propelled by horsepower-forward engines, while this new one is torque-forward. It’s not better or worse, just different.

With a door opening suspiciously similar to the 370Z’s, the new Z requires a conscious duck to enter. Inside, the driver faces a reconfigurable 12.3-inch square screen for the main instrumentation, an 8.0-inch center touchscreen for the Apple CarPlay and Android Auto stuff, and three circular supplementary gauges atop the dash center. These round instruments, throwbacks to the first Z-cars, are a bit discordant with the otherwise squarish shapes in the interior. But hey, discordance can be fun.

The exterior does a fantastic job of capturing elements of several Z generations and recombining them into something fresh and satisfying. It’s gorgeous, even if the available black roof is gimmicky and seems to stop arbitrarily on the tail. And maybe the side spear trim along the roofline is more a distraction from this car’s sweet shape than an enhancement.

Crack a femur depressing the clutch, press the start button, and the V-6 thrums to life. There’s not much of an exhaust note (the 240Z had a magnificent one). But the sensation of torque rising up through the six-speed manual transmission’s shifter and into the driver’s right palm is simply intoxicating. Blip the throttle and the whole powertrain twists a bit, an announcement that this is a real, mechanical thing built to scamper and skedaddle. It is not a simulation.

With the same 100.4-inch wheelbase as the 370Z, this is a short rear-drive car with loads of torque and big-chunk Bridgestone Potenza S007 tires. In the Performance model driven here, those tires are P255/40R-19s in front and P275/35R-19s in back, sizes also found on the Toyota Supra, the Z’s closest natural competitor. That’s an adequate but not overwhelming amount of rubber. The base two-wheel-drive Porsche 911 Carrera, for instance, uses a 295-mm-wide rear tire and is down 21 hp and 19 lb-ft on the Nissan.

The base Sport-model Z has 18-inch wheels and P245/45R Yokohama Advan tires at all four corners. It also lacks the mechanical limited-slip differential of the Performance version. Interestingly, Nissan lists the Performance as having a “sport-tuned” suspension while the Sport doesn’t. That’s goofy.

It’s easy to overcome the rear tires, which the Z would fry like bologna on a cast-iron skillet if not for the intervention of a well-tuned electronic traction control. Electric power steering has evolved to the point now that its assist is often indistinguishable from that of hydraulic systems. In the new Z, the steering rack runs at a rather tame 15:1 ratio but with excellent communication and feedback.

Dive into a corner and the car will push its nose, but that can be balanced by adding some grunt from the deep torque well. The traction control doesn’t step in until there’s some noticeable tail movement, and it doesn’t intrude harshly. Switch the traction control off, and the tail needs considered concentration to keep tidily mannered.

There are no surprises in the suspension design. The geometry of the front cast-aluminum double-wishbone system has been tweaked, while the rear multilink setup transfers over practically intact from the 370Z.

The Z would benefit from one bit of missing legacy technology: the Super HICAS rear steering system that made the Z32-generation 300ZX Twin Turbo a rocket ship through slalom tests and a joy on back-road romps. It has worked well on various Nissan GT-Rs too. With its complex hydraulics and tuning challenges, Super HICAS must be an expensive technology to optimize and include. But electronic traction and stability controls aren’t good substitutes, and Nissan ought to hit the wayback machine and resurrect Super HICAS for the 21st century.

With the launch control used to reasonable effect, the manual-transmission Z goes to 60 mph in 4.1 seconds and completes the quarter-mile in 12.6 seconds at 115 mph. Competitive times, if not world-beating. And this is clearly the quickest production Z-car yet built—much quicker than the 370Z, with its 5.0-second rip to 60 mph and 13.6-second, 106-mph quarter-mile performance. The 2023 Z is entertaining, but don’t use it to challenge things named Plaid or Mustang GT.

Dancing between braking and throttle, the Z rewards talented and experienced drivers. But even they will spend more of their time in traffic than seeking out perfect lines across Angeles Crest Highway or Tail of the Dragon. The Z is suspended stiff, the tires growl a bit, and the clutch needs a heave. Maybe this Z would be a better commuter if equipped with the Sport’s not-sport-tuned suspension and Nissan’s version of the Mercedes nine-speed automatic transmission; maybe not.

The brakes, by the way, are excellent and sustain well when hurtling down a mountain road. The Sport uses two-piston calipers in front, while Performance models go with four pistons on each 14-inch front disc.

Prices for the new Z, on sale now, start at $41,015 for the not-so-sporty Sport model. The Performance version goes off at $51,015, which is about right considering its bigger wheels and tires and better brakes. Nissan will also make 240 models called Proto Spec and sticker them at $54,015. Pricing is aimed directly at the six-cylinder Supra. Unlike Toyota, Nissan doesn’t resort to a less powerful four-cylinder for its base model. Regardless of trim level or price, every new Z comes with 400 hp.

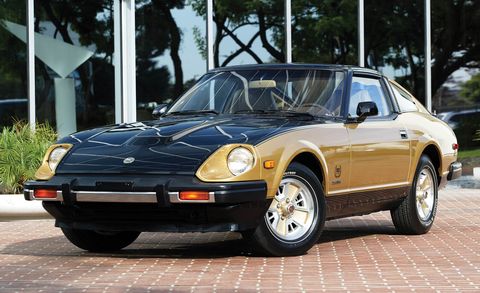

Back in 1970, the Z-car was exactly what Nissan and the Japanese auto industry needed. The gauche 1979 280ZX is easy to dismiss now as flabby and overwrought, but it was perfectly attuned for its double-knit, disco-ball era and sold by the bushelful. The first Z31 300ZX appeared for 1984, embracing digital doodads like one giant LED. And the Z32, even 32 years later, remains a startling piece of work.

But this new Z feels as if it’s lingering at the party. It’s among the last of its front-engine, rear-drive breed. It has neither gone full retro—bringing back T-tops would’ve been awesome—nor embraced electrification, hybridization, or all-wheel-drive-ification. And it hasn’t been reimagined as an electric crossover, though the name E-Z is obvious. This isn’t a car of its moment; it’s fighting the moment in which it’s stuck.

That fight is noble, even if it’s futile Black Knight stuff. The world ought to be able to embrace this thing, even as it faces its sunset. And if Nissan does another Z beyond this one—five, six, 10 years from now—it inevitably won’t be anything like this. That’s both tantalizing and a pity.